One of the most critical pieces of survival gear to have is rope, which you should have in your Bug Out Bag for wilderness survival.

But what if you lose your rope or run out? That is where knowing how to make rope from plants comes in.

*I want to point out that rope making is something that humans have known for a really long time. Prehistoric people started making ropes at least 1.8 million years ago! How do we know this? Because archaeologists have found imprints of rope in rocks and clay. (Source)

If our ancient ancestors could figure out how to make rope from plants, there is no reason we can’t do it today. The only skill that modern men are lacking is patience!

Step 1: Find Your Plant Fibers

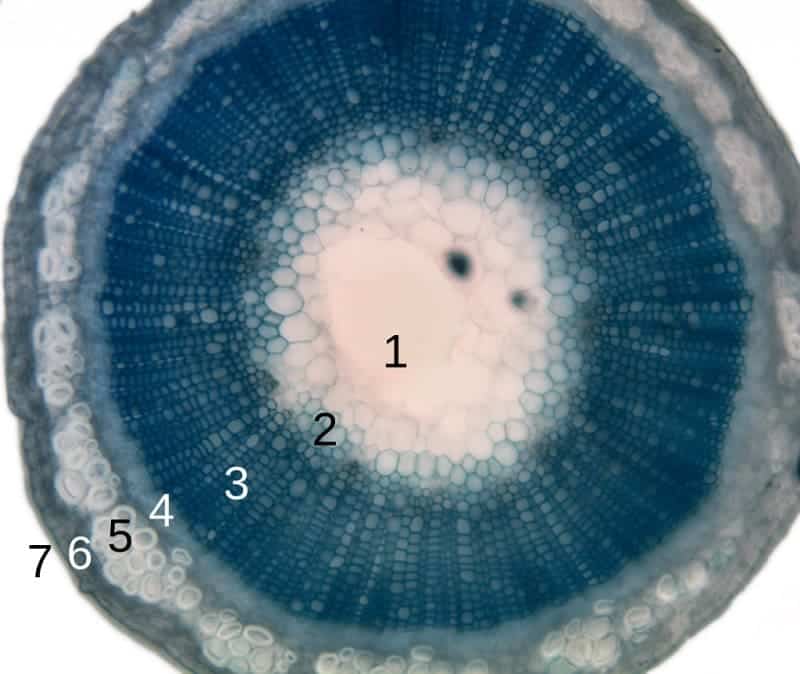

First off, let’s start with what is fiber. If you understand this, you can make rope out of plants even if you can’t identify the plant in question.

Plants are mostly made of two components:

- Starches: These are the nutrient parts of a plant. They will dissolve in water.

- Fiber: These are the parts of a plant that give it structure. Insoluble fibers will not dissolve in water.

All plants consist of fiber. However, to make a strong cord, you want to choose plants that have the strongest fibers.

Some of the top plants for making cordage include:

- Stinging nettle

- Yucca

- Milkweed

- Dogbane

- Western red cedar

An advanced survivalist might take the time to memorize the best plants for making cordage in the wild. But what will you do if you can’t find these plants?

I think memorizing which parts of a plant have the strongest fibers is a lot more realistic.

Best Parts of Plants for Making Rope

- Bark Fibers: You do NOT want to make twine out of bark. You want the fibers from the INNER bark of a tree! They are also very long fibers, so are easier to use for making rope than shorter fibers.

- Stalk Fibers: These fibers are also robust and long. While they don’t have the strength or length of bark fibers, stalk fibers are easier to access and use.

- Grass Fibers: These fibers are pretty short and not very strong. However, it is straightforward to process grass fibers, so they are a good choice if you need to make rope quickly and strength isn’t a significant issue.

Plant parts like leaves also contain fiber. However, leaf fibers generally are very weak except for a few species.

To put this in perspective, think celery fibers vs. spinach fibers. Celery is a stalk, whereas spinach is a leaf. Which would you rather make rope out of?

* I learned a lot about fibers during a papermaking course I took. It is amazing how many survival skills you can learn if you keep your mind open!

Step 2: Separating the Fibers from the Plants

To make rope, you need to separate the fiber from the plant. Otherwise, you’ll end up with a lot of starches in your rope. Those starches will weaken the rope. The moment it rains on your rope, you can count on it to dissolve!

There are a few ways to separate the fibers from plants to make rope:

Method 1: Boil Fresh Plants

If it is springtime and you only have fresh plants available, you’ll need to boil them. When you cook the plants, the starches will dissolve into the water. You dump out this water and wash the boiled plants. You’ve got to wash them thoroughly to get rid of any starches that might be remaining. What you end up with is pure fiber.

Some people half-ass this step and just soak the plants in water. This works okay if the plant is fibrous (think woody stalks or inner bark). However, you’ll still end up with a lot of starch remaining, and your rope won’t be as strong.

Method 2: Find Dead or Dry Plants

This is great if you use grass or stalks as your rope-making fiber. Once the plant has died and dried up, the starches will have dried out, too.

If you are using stalks for your fiber, choose plants that have tough, wood-like outers. Lay the dry stalks out on a flat surface. Using a rock, pound the stalks so they split lengthwise. Do not try to cut the stalks open, as this will cut the fibers.

Now, you can use a knife or sharp rock to scrape out the softer fibers from within. Discard the outer bark and use the inner fibers.

Note: Some people find it helpful to soak stalks to make it easier to separate the fibers from the outer bark. This is fine. However, NEVER USE WET FIBER TO MAKE ROPE. It will shorten when it dries, thus causing your rope to unravel and weaken.

Method 3: Drying the Plants Yourself

If you aren’t restricted by time, then you can hang the plants to air dry. Much of the starch will dry out of them, leaving behind mostly fiber. Just as if you were using dead plants, you’ll need to pound open stalks and scrape out the fibers.

Method 4: Stripping the Inner Bark of a Tree

The inner bark of trees doesn’t contain much starch at all. The inner bark also has the strongest and longest of plant fibers. So, this is the best way to get your plant fibers for making rope in the wild.

Some trees – especially red cedar – have long, stringy fibers. You remove a long section of the bark (you’ll want a survival knife to do this) and then peel off long fiber strips.

If the fibers are tough and can’t be broken into thin strips, you can soak them in water and then strip them.

Important: When I say “inner bark,” I am talking about the part known as the bast or phloem of the tree. In a true survival situation, you can strip away as much of the phloem as you need. If you are just testing your skills, look for trees with dead bark. Or, if the tree is living, only take a few thin strips from it. Taking too much phloem can kill the tree.

Step 3: Buffing the Fibers

Depending on the type and part of the plant used, you might be able to make rope immediately from the fibers you sourced. However, you’ll probably need to do something called buffing first.

Buffing is a step that softens the fibers so they are more flexible. It also helps to remove any remaining woody bark.

Just roll the fibers back and forth in your hands to buff them. Or, I prefer to put the fiber strands on my thigh and rub my hand back and forth over them.

You should see the fibers becoming fluffier and stringier.

*Just because the fibers are becoming thinner, it doesn’t mean they are getting weaker! You want the fibers to be very thin and fluffy. The thinner and fluffier the fibers are, the better you can twist them together. The twisting is what gives the rope strength!

4. Wrapping Your Fiber into Rope

Now, it is time to wrap your plant fibers into rope! There are a few ways to do this, and none of them can be explained well in text. So, here’s a video that will show you how to wrap natural fibers into rope.

This is a great survival skill to know and could save your life. You might even start trading the rope you made for supplies. But keeping some strong rope in your Bug Out Bag is still a good idea.

If you aren’t sure what rope is best, here’s the Survivalist’s Guide to Rope.

Have you ever tried making rope from plants? How did it go? Let us know in the comments.

I thing he’s a good explainer. I am definitely going to try this, maybe today, soon. That work thing stops me from doing it now.

Braiding with a three ply reverse twist makes a fine bow-string. Hemp is best; unfortunately harvesting wild hemp is considered ‘manufacture of narcotics’ in some states.

Can you use fiber from banana stalks

I’ve never tried this myself (don’t live somewhere with bananas!) but banana stalks are very fibrous. It should work well for rope.

Starches are insoluble.

**Until it’s boiled, at which point most plant starches will swell and burst out of their crystallized granular structure releasing the stored glucose and rehydrating. When finding plant materials that have already detached from its living body, sometimes dessicated, but not yet decomposed, the starches will have been recycled into the foodweb via microbes. I’ve been on my cordage making from foraged natural materials journey for about 6 months now, it all started when I realized the umbrella sedge that has prolifically grown in my gardens since taking some from my great grandmothers house so many years ago is truly a papyrus, cousins to the classic Cyperus papyrus (always had the assumption due to its look but plants surprise me with how some look so similar but can differ so much in the details)—anyways, naturally, I needed to learn how to make papyrus paper from this Cyperus alternifolius the way the Ancient Egyptians would (this opened up a whole different journey of learning how to bleach plant materials correctly with caustic soda and hydrogen peroxide, and yes I sat in a Starbucks for 4 hours jotting notes on the chemical reactions that take place and demystisizing the industrial process from numerous paper mill publications haha), a successful processing of the long (6 feet at their tallest) reeds cut into thin strips and a solid week long soak (because I forgot about it) in the peroxide-hydroxide bleach solution ultimately ended in a single, 5inch by 5inch piece of perfect paper that I will be painting a Kawaii frog on for my grandmother’s birthday next month. The remaining bleached reed strips still sit in a jug of water months later with no sign of rot, mold, or deterioration. Thinking, what could I do with all the beautiful strips of the peeled reed skin? Set forth rope making, turned newer journey, how to spin yarn/thread with a manual spindle?? Still looking for the perfect plant that makes a fiber easy to process, thats not too smooth so that it doesnt fall apart when twisted, and that’s readily available to me. Dessicated sea oat rhizomes that are rehydrated are showing some good promise. Speaking of, soaking fresh plant stalks to make them more workable in obtaining the fibers is a process known as retting, really you’re half rotting them so the bast fibers (#4 in the article’s cross section photo) loosen and can separate easily from the core. Also, I’ve made successful cordage from damp plant fibers before with no shortening of the final product upon being totally dry. Some species’ fibers I’ve found actually twist more readily when dampened, and when twisting tight enough the bit of water is usually wrung out or absorbed by my hands. Wet, like sopping wet, fibers definitely wouldnt attempt, but I’ve really found no compromise of a cords integrity less it were made from freshly cut green plant matter. Lastly, just from experience, the easiest plants to start cord making with are definitely long stemmed grasses or stalked non-grass monocots, left to dry crispy, then soaked for an hour in water, splicing is easy with this material as well. <3 xoxo

This was really useful I’ve been learning to craft flint tools but I need rope to secure the flint

Thank you for this handy summary. As we were driving along a remote rural road earlier today, I noted the township had mowed the shoulders of the roads, which don’t get much attention normally. This however opened to view, the tall wild plants growing out of the ditch. Among these are nettles, elderberry (in bloom), milkweed, and motherwort to name just a few. I’ve used nettles in many forms but have never collected it for fiber, one of those items on my to-do list for someday. Your article rang home that someday may be now. Will get back out there and collect a bundle. Now to get a pot big enough to boil all that. My biggest is a canning kettle so likely will have to do several batches and coil them around. Thanks again for this article.

We’d love to hear how it goes. Maybe share it in our Facebook community? https://www.facebook.com/PrimalSurvivors/ 🙂