A lot of people throw the word “permaculture” around like it’s the answer to all of our food production woes.

Unfortunately, like everything else, once you scratch below the surface it isn’t that simple.

Tremendous benefits and food production capabilities are achievable while practicing a permaculture philosophy but, to put it bluntly, it ain’t infallible.

We’re going to explore what permaculture is all about and examine its many strengths, but also pay attention to its weaknesses.

Let’s get to it.

Wait, What Is Permaculture?

While the principles of this style of food production have been employed for the history of humanity, the term “permaculture” was not devised until the 1970’s.

Bill Mollison was a born-and-raised Australian native who spent ample time in the bush. While living off the land he became enamored with how wildlife could survive off an incredible network of food production and sustainability.

Times of hunger and drought existed, but the wildlife existed in an interconnected food network that did not need the hand of man to guide things along.

The “Father of Permaculture” said that permaculture is a

…philosophy of working with, rather than against nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labour; and of looking at plants and animals in all their functions, rather than treating any area as a single product system.

So basically, we look to nature as a guide for how to procure and produce food, and an elimination of the “food chain” to be replaced with a “food web”.

Principles of Permaculture

Typically you’ll find a list of 12 principles that define the permaculture philosophy.

- Observe and Interact

- Catch and Store Energy

- Obtain a Yield

- Apply Self Regulation and Accept Feedback

- Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services

- Produce No Waste

- Design from Patterns to Details

- Integrate Rather Than Segregate

- Use Small and Slow Solutions

- Use and Value Diversity

- Use Edges and Value the Marginal

- Creatively Use and Respond to Change

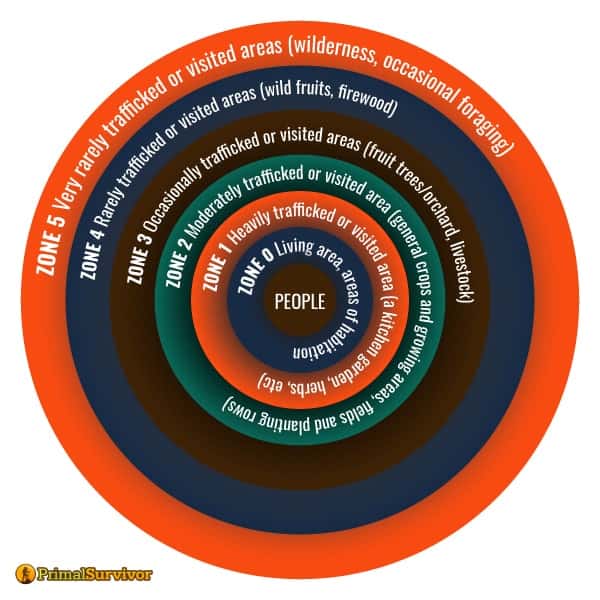

On top of that permaculture largely bases itself off of a list of “growing zones”.

If you imagine a series of concentric circles with a living area or home at the center, you’ll find the areas of heaviest use are closer to the living area and then fade in use or traffic until the outermost ring is essentially wilderness.

The zones are:

- Zone 0: Living area, areas of habitation

- Zone 1: Heavily trafficked or visited area (a kitchen garden, herbs, etc)

- Zone 2: Moderately trafficked or visited area (general crops and growing areas, fields and planting rows)

- Zone 3: Occasionally trafficked or visited areas (fruit trees/orchard, livestock)

- Zone 4: Rarely trafficked or visited areas (wild fruits, firewood)

- Zone 5: Very rarely trafficked or visited areas (wilderness, occasional foraging)

Sounds good, and it’s an excellent perspective to take when considering food production… especially if we can’t rely on supermarkets to produce food and produce for us. But is it really that simple?

Starting Your Permaculture Garden

All of the key points and elements in our guide to starting your survival garden will apply to a permaculture garden, so that’s a big plus!

To refresh ourselves, the difference with a permaculture garden is that it exists largely on its own without much of our intervention and practices a maximum sustainability approach.

Ultimately we want the variety of plants to benefit one another more directly than in traditional gardening practices. The Three Sisters is a commonly known method of integrating permaculture practices into a garden.

Native Americans often used maize (corn), squash, and beans as primary food sources and grew the plants together instead of the neatly organized rows we’re used to seeing. The low-growing squash would provide ground cover and minimize the presence of weeds for the corn to grow tall and without competition, while the corn provides a supportive trellis for the beans to climb.

Ultimately the beans help to replenish and “fix” the soil with nitrogen, a vital component of plant health and food production. This is a perfect, simple example of how to employ permaculture techniques in your garden.

Remember, the less we need to intervene with the growing the closer the garden is to ideal. This isn’t hippie mumbo jumbo!

My own garden tends to outperform my neighbors because I let the plants do what they need to do and step in minimally. I also never use pesticides and minimize my fertilization to a twice-yearly sprinkling of compost.

Permaculture is about creating a sustainable growing area with no need for constant intervention; keep this in the forefront of your mind when establishing your own permaculture garden.

Suggestions for Establishing Growing Zones

The growing zones mentioned above do not need to be in a circular pattern; that’s purely an illustrative idea!

The point of these zones is to plan your garden in the order of most used to least used. Here’s a better outline with suggestions.

Zone 0

Meant for: Your living space, but this is also a location where you can store food, tools, and other necessities. At your home this is… well, your home, but in the field it can be your primary camp. We spend most of our time here.

Suggestions: Keep this area organized and neat as much as you can so that when you need a tool you can grab it and go

Zone 1

Meant for: The location where you’ll plant material like herbs and vegetables. The key to establishing your Zone 1 planting is to consider the plants that need the most attention and will have the most use. If you grow herbs outside your kitchen now, this is a Zone 1 garden.

Suggestions: Herbs tend to favor dry and hot conditions so keep them separate from other more temperamental areas of the garden. This Zone is a good place to establish plants that require regular care and harvesting like tomatoes, radishes, cucumbers, and leafy greens.

Zone 2

Meant for: Crops with a much longer period before you can harvest. You’ll need to check on plant health every few days based on the condition of the plants on each visit. At your home now this is the vegetable bed you’ve got in the backyard you inspect after work every few days.

Suggestions: Pest problems are infrequent but can be disastrous, so make your visits here attentive ones.

Grow vegetables like pumpkins, onions, garlic, and potatoes. These crops need watering less frequently than your Zone 1 crops, but should still be easily watered if the need arises during very hot or dry conditions.

Zone 3

Meant for: Fruit trees and livestock, far enough away from your living area that noises and smells won’t be an issue but close enough to visit when needed.

Most fruit trees require heavy maintenance once a year but can be ignored after that, except for inspecting the conditions of fruit and tree health.

Live stock can be temperamental depending on what you have. The fruit trees and backyard chickens at your home now are Zone 3.

Suggestions: Stark Brothers is an authority on all-things fruit trees, so check out their guide on starting your own apple orchard. Many are great for fresh eating and also for storage and are ideal as a food source over the winter months.

If your chickens are free range keep them away from your seedlings and vegetables producing fruit; goats can likewise cause tremendous damage.

Zone 4

Meant for: The place where you don’t really need to do anything but maintenance and upkeep as you have time for it. Look for firewood and wild fruits, possibly wild game depending on the size of your territory.

Many houses have a “Zone 4” as the more wildly growing barriers separating yards.

Suggestions: A good place to experiment with new plants. In the right conditions this is an ideal place to forage mushrooms. Keep the area clean and easily traveled by removing undergrowth and using firewood as necessary.

Zone 5

Meant for: “The wilderness”; at your home it’s the neighbors yard! You don’t do much in this area except to use it as a place to seasonally forage, to inspect your boundaries, and to get some peace and quiet to yourself.

Suggestions: Little is done here except for occasional foraging, use it as a place of quiet… or as a location to watch the outside world from relative safety.

Be Aware of the Limitations of Permaculture

As a devoted plant nut, what I’m about to say is gonna hurt…

No matter how great your set-up, plants need your help to produce anything worthwhile!

There, I said it. And it hurt. Permaculture offers the promise that you can produce enough food to sustain you and yours without hardly lifting a finger, and that’s crazy.

Growing a crop of fruit or vegetables requires diligent effort. Those peppers might grow by themselves, but they’ll be devoured and devastated by pests and bugs without your attention.

Permaculture offers some weird belief that with the right native crops and variety of insects and natural predators your pest and fungal problems will take care of themselves.

That’s just not true, and I’ll tell you why.

In doing some additional research on writing this article I stumbled on this excellent article countering some of the oft-endorsed benefits of permaculture. What stood out most to me as an unwelcome smack in the face was, “… agriculture does not exist in nature.”

Suddenly my lofty ideals of an interconnected world that takes care of itself were thrown for a loop. Mankind didn’t remain stationary (except in a few exceptional cases) until we developed the practice of growing a reliable crop of food.

That brings us to look at the negative sides of permaculture:

- Relies on a wide variety of foods available for harvest at different times of the year but never produce significant crops

- Despite the claims that the crops will take care of themselves, they simply won’t; prepare to get to work in a permaculture garden, especially if your well-being depends on these crops

- Tends to require ample amounts of space to succeed

- Sustainable but unreliable method of food production; you’re not going to use additional resources to grow your food but a solid harvest is not guaranteed

Wait, so why the heck am I telling you to get into permaculture if has these drawbacks?!

Because it works as long as you wash away the Disney-infused idea that everything will figure itself out magically.

Why Use It?

Let’s look at two scenarios for why you should get into starting a permaculture garden. One is that you are living somewhere now and have a bit of space to get started, and the other is if you’re in a SHTF-type scenario and need a reliable source of food.

Starting From Your Home Now?

Great! Starting your own tiny version of a permaculture garden has the tremendous benefit of getting your ass outside and in the outdoors. I mean, what else do you need?

As Billy Mays would say, “But wait, there’s more!”, because there is. You get fresh and naturally-derived produce to enjoy at your table, something you’ve watched and helped to grow in your very own backyard (or wherever you’ve got space to grow food). Additionally you have the opportunity to watch, love, and enjoy the natural world existing right around you with zero need for your intervention.

Throw depression and lackadaisical what-do-I-do-today’s out the window.

If you’re upset over something, spending time outside is proven to be an effective pick-me-up.

You’re in a SHTF Scenario?

Well, I mean, what else is there to say?

Growing your own food might require additional fertilizers and a more hands-on approach than permaculture wants to admit, but you’ll have safe, reliable food to eat up. That’s pretty great, isn’t it?

You’ll have a lesser impact (and a smaller area of visibility) if you employ permaculture practices in your garden so that the food seems to be naturally present and not man-made or grown. Beyond that you’re maintaining the ecological health of your area by employing low-impact growing practices.

While any type of food production requires an investiture of time something that delves into permaculture will require less time than other methods. That frees you up to do other, bigger, more important projects.

Making the Most of What You’ve Got

Is permaculture the solution to all of our gardening woes, and is it going to make our life after the SHTF a relaxing one full of self-producing food crops? Probably not.

But it will shift the perspective of food production and cultivation, and its reliance on non-invasive, non-destructive gardening technique is a powerful and beneficial one. The ultimate benefit of all of this is that it puts you, me, and anyone else with a shovel back outdoors and encourages us to look, listen, and interact.

It’s good for your health as-is, but in the right scenario that kind of connectedness to your environment can be the difference between life and death, or starvation and comfort.