When you start homesteading, you find that there is a use for everything and stop throwing things away.

There are even a lot of uses for ash from your wood stove – including making soap. If you want to try this homesteading project, here are detailed instructions for making wood ash soap.

Introduction to Soap Making: Lye + Fat = Soap

Soap is made by mixing lye (a high pH, alkaline caustic substance) with fat (a weak acid). The chemical reaction between the two produces soap, which is great for cleaning almost anything.

You might have even heard of campers or cowboys putting ashes in their cooking pots after eating.

The ashes mixed with the leftover cooking fat produce a crude soap.

Just rub it around, and the dishes come out clean (I wouldn’t wash my body with this, though!).

Lye

You can buy lye at specialty stores. However, this lye is sodium hydroxide. By contrast, traditional lye made from ashes is potassium hydroxide.

Wood ash lye is much less caustic than the commercial stuff you can buy. It still works great for making soap but will be softer and more oily.

You won’t get as many suds from wood ash soap either. There are tricks you can do – like playing with ratios and adding salt – to make a harder, less oily soap.

Fat

Any fat will do for making wood ash soap. Traditionally, pioneers would use lard or tallow to make soap. Learn how to render your own lard/tallow here.

You can also buy quality grass-fed beef tallow on Amazon.

If you want a nicer-smelling soap, try using other oils, such as coconut, olive oil, cocoa, or shea. You can also add scented oils to your soap.

When first getting started, though, I’d stick with a basic soap. As you gain experience, you can experiment with different ingredients.

How to Make Wood Ash Soap

Supplies:

- Ash from hardwood fire: I’ve found that maple, ash, and hickory work best, but any hardwood will do. You can also use softwoods. However, these contain a lot of resin. You’ll end up with a liquid soap (great for washing dishes and laundry) instead of a bar soap.

- Soft Water: Normal tap water contains too much chlorine and minerals to make soap. You can use distilled water or collect some rainwater to make your soap.

- Plastic or Wooden Bucket: With a hole cut in the bottom, minimum 5-gallon

- Pot: Do NOT use aluminum. A chemical reaction between the lye and aluminum will occur — and the lye will also eat through the pot. Stainless steel or enamel work well. You can also use a crock pot.

- Fat: Lard, tallow, and oil

- Soap Molds: Wooden boxes work well. You might want wax paper for lining the boxes!

- Glass measuring cup

- Wooden spoon with long handle

- Safety Gear: Gloves, goggles, old clothes, rubber boots (seriously, lye is caustic and will eat through your skin and clothes!)

Step 1: Gather Ashes

To produce a good soap, you need hardwood ashes that have been burnt throughout. That means the ashes should be WHITE. The black chunks of wood contain too much carbon.

One (messy) way to get pure white ash is to put all of your ashes in a sieve. Sift the ashes through the sieve – the white ash will fall out, and the black chunks will stay out.

Step 2: Make Lye

There are two methods you can use to make lye from hardwood ashes. The first method is more straightforward but doesn’t produce as good of results.

Method 1:

- Mix ashes with softwater

- Boil the mixture for about 30 minutes

- Let the mixture sit for at least 3 hours (though overnight is better).

- The ashes should settle to the bottom of the pot.

- Wearing gloves, collect the liquid from the top of the pot. It should be yellowish/brown, much like apple cider vinegar.

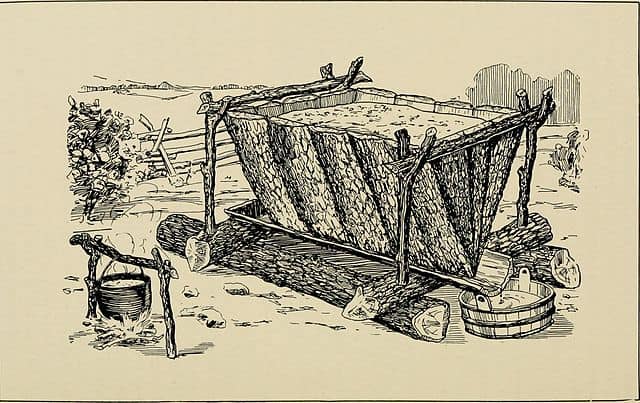

Method 2 (Making a Leaching Barrel) :

With this method, you will pour the water through the ash. The water which drains off will contain lye. It’s easy to do, but be patient – it takes time for the water to drain through the ashes!

- Get a plastic bucket, wooden barrel, or big clay pot. Poke a finger-sized hole in the bottom.

- Cover the bottom of the barrel with small stones. Put a layer of dried grass or pine needles on top of this. Then, put your hardwood ash on top of this.

- Pack the ashes down as much as you can.

- There must be at least a few inches of headroom on top of the barrel.

- Prop the barrel up on some boards. Position a bucket or pot underneath to catch the lye.

- Pour soft water on top of the ashes.

- About 6 hours later, you’ll see water coming out of the barrel. Yes, it takes this long! Don’t try to rush the process by adding more water.

Ratios of Ash to Water:

There are a lot of different measurements used for making lye. This is because it can vary depending on the type of wood you use.

Generally, 10 cups of ash = 1 gallon of lye water.

Some of the water does stay absorbed in the ashes. So, pour 1.5 to 2 gallons of water through your leaching barrel to get 1 gallon.

Testing Strength of Lye Water:

This step is completely optional. However, newbies might get peace of mind by testing the pH of their lye water.

Lye water should be about pH 13. You can get pH testing strips to check this. Or, for a more traditional testing method, just put a chicken feather into the lye water. If it dissolves, then the lye is strong enough.

If your lye water isn’t strong enough, then you can pour the lye water back through the leaching barrel. Recollect the water and test it again.

Don’t worry if the pH isn’t exactly 13. Stronger lye soap can be used for tougher tasks like washing clothes. Weaker lye soap can be used for washing your body.

Step 3: Concentrating the Lye

Boil your lye water in a stainless steel (not aluminum) pot. One gallon of lye water should reduce to ¾ cup. This will take several hours!

How will you know that your lye is done? It should be thick enough that an egg can sit on top of it.

You’ll need the lye to be hot and bubbling while you do step 4.

Step 4: Add Your Fat

- Carefully heat your lard or oil.

- Slowly add the hot lye concentrate to the hot fat. (Note: Add in this order to reduce the chances of splattering)

- Continue to boil the mixture. Stir constantly for 3 minutes. It should be thick like porridge but without any chunks.

- If you are making large amounts of soap at once, add the fat gradually, stirring for several minutes each time you add more fat.

- Reduce the heat so the lye/fat mixture isn’t boiling anymore but is still warm. It should be kept around 100 degrees F.

- Stir the mixture for 1 minute, then let it sit for 10 minutes before stirring again.

- When the mixture is a uniform golden brown and doesn’t make colored streaks when stirred, it is ready for pouring. It might take several hours before it is ready. Keep it warm during this time!

- You’ll know the soap is ready to be poured when you draw a line across it with your spoon and see a line (indented, not colored streak).

- If you want to add anything to your soap (scented oils, dried herbs, coffee, etc.), this is the time to do it.

Ratio of Fat to Lye:

Making soap requires a lot of trial and error to get it perfect. A good ratio to start with is 1 cup of fat to ¾ cup of concentrated lye. If you want to get scientific about it, then check out this lye: fat table based on saponification.

Step 5: Pour Into Molds

Now, you are ready to pour your soap into molds! Wooden boxes work well, but you can also use plastic containers. Line wooden boxes with wax paper first to make the soap easier to remove.

You don’t want your soap to cool down too quickly, or it will become brittle. After pouring, cover the mold with a towel to retain some of the heat. Remove the towel the next day.

The soap must be set for several days (ideally 7 days!) before you remove it. You can cut the soap to size beforehand, though. It will be easier to cut when it is still soft.

6. Using Salt to Make Harder Soap

Wood ash soap is usually really soft. Depending on the type of wood used, you might not be able to get it to set into a bar at all.

One trick for making hard soap is to add salt. Use ½ tsp of salt per pound of fat (1lb is roughly 2 cups melted fat). Note that some soapmakers use a lot more salt – as much as 3 tsp per cup of fat.

Just add the salt when you mix the melted fat into the lye. Make sure you are stirring thoroughly so the salt completely dissolves.

Troubleshooting

- Soap won’t thicken: Try adding more lye. If this doesn’t work, then it might be the quality of your wood (soft wood won’t make a hard soap). You can add salt to harden the soap.

- Mixture is greasy: Try increasing the temperature and mixing again. If that doesn’t work, then try adding more lye.

- Brown liquid is running off the soap in the molds: Just let the liquid drain off. Next time, add more fat to your soap.

- The soap has white ash on it: This is lye dust forming on the soap. Just wash it off and use the soap. Or, prevent it by keeping your soap covered while drying so the lye doesn’t come in contact with air.

- Soap won’t make suds: Unfortunately, homestead wood ash soap doesn’t make much foam. It will still get you clean, though. Try using a loofa to mimic the sudsy sensation.

Have you tried making soap from wood ash? How did it go? I’d love to hear what types of wood and oils you used and their ratios!

CC BY 2.0) by necrocake “ash water / drip lye container” (CC BY 2.0) by rickbradley “Let’s Do This” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by savor_soaps “Molding the Soap” (CC BY-ND 2.0) by madaise “Ready to go…” (CC BY-ND 2.0) by madaise

Is it okay to boil down the lye water in your house? It doesn’t put off toxic fumes, does it?

The instructions for the lye concentration are confusing.

In step 2 there is what seems like reasonable, useful information – a pH of 13.

But then in step 3 we get an ambiguous “One gallon of lye water should reduce to ¾ cup”. What? Is that starting from lye water that was already at a pH of 13? Or should that really be a guideline in step 2 about estimated average of the lye water of unknown concentration from one of the extraction methods?

I guess the instructions are saying to make a mixture of lye water from the ashes that has a pH of 13 and then boil a gallon of that down to 3/4 cup? At which point the solution will have a pH over 14. Is that right?

It would be better to give the requirements directly, like “Mix 100 grams of pH 13 lye water to 300 grams of oil”

Thanks the writer. 100 percent in details .

I remember my mom making soap. She used fat from pigs or beef which ever we had. We used it for washing clothes and ourselves. we burned cottonwood and coal.

Hey I live in a community of people who (for reasons I would prefer not to get judged harshly for) burn just about anything in a nightly bonfire. For example, plastic coated paper plates, aluminum cans, newspaper, magazines, envelopes, cardboard boxes, dimensiinal lumber, chairs, tables, trees, weeds, shrubs, cypress, boxwood, pine needles, leaves, yard waste, chicken, spoiled lefticers, fast food bags, containers, receipts, file folders, motor oil, gasoline, glass, HDPE plastic, Poly propelyne, isopropyl alcohol, rum, denatured alcohol, cosmetice, tupperware, clothing, bedsheers, dig and cat waste, litger, rubber, pens, pencils, retail packaging, bubblewrap, plastuc bags, pkastic containers, planters, yard signs, nails, nuts, paper, printer paper, usb cables, bolts, all manner of garbage, etc.

IF I take the time to sift the ashpile removing all remaining solids after the fire goes out and the embers cool or become ash, can the ash from these bonfires be used for soap making?

Definitely not! You should burn wood separately and only use that ash for soap making.

Yeah it will make soap. Would YOU want to use the soap made. Maybe not. But it will make soap.

Remember to keep the soap very well insulated after mixing the lye/fat and pouring it into the mold. Soap will not harden if it loses too much heat (adding lye to oil produces heat) during the setting up/hardening process. Wrap with a heavy blanket and use wood molds, or anything that holds heat.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge. I made lye water using an unglazed terra cotta pot, and the water has a deep orange color. It has been sitting for about 12 hours now, and it doesn’t appear that this is from any solids that are settling out. Do you think the lye water is safe to use?

Thank you very much for this.

I will try it.

I used John Seymour’s recipe from his Complete Guide to Self Sufficiency book.

It came out like soap but maybe it needs a long time to cure.

500g clarified fat at 32*C

1 cup olive oil

1 cup of groundnut oil

1 cup of rainwater with perfume

Add the water and perfume to the oils and bring to 32*C

Then take 2 tablespoons of wood ash lye in a half cup of rainwater at 32*C.(1/2 cup of liquid total)

Then pour the lye liquid into the fat mixture.

Keep stirring until it leaves a mark with your wooden spoon.

NileRed’s video on youtube is pretty informative

Sorry, I meant “too.” NileRed’s video(s, he has two) is informative on how the soaponification process happens, and the different parameters for the making of soaps. I actually tried making my own soap by the “cold process,” but it was actually this recipe that I had success with. I used Cottonwood ash on the first one, and it was pretty soft, so now I’m trying it with apple wood ash.

Ashes, one key thing, if your ashes have sat in your fire pit through rain or fire put out with water much of your lye may have been rinsed out already. Gather your ashes from a clean fire pit so you are not using that old rinsed ash.

Safety! don’t skimp on the safety gear lye can blind you or strip your skin off. It is just as dangerous as battery acid in a car battery. Maybe even a dust mask or covid mask while gathering and sifting the char out of the ashes.

I add salt to the lye solution until it won’t dissolve anymore. Then add to oil excluding the undissolved salt. As I understand it, the salt (NaCl) reacts with the ash lye (KOH) to make NaOH which is typically used to make hard soap bars. Still it is very difficult to get the ash lye amount correct as it varies so much depending on the wood and extraction procedure.

I have made cold processed soap for decades. I have often considered making ash lye soap but did not try it until asked to demonstrate the process. I have been working on a batch for a few days now and was able to make the soap yesterday. The lady I spoke to about the demo insists her grandmother made it into firm bars. I don’t think mine will ever firm up even with the addition of salt. I still have 10 days to see before the demo.

It seems like there can be so much variability in the lye solution that it makes the most practical sense to prepare a very large batch of lye, so that you can do a few test batches. Once you do a few test batches then should more or less have a reliable fat to lye ratio to run with.

Have you made soap using these directions? Did it turn out? I’m afraid that without the proper amounts of oils and butters to react with the amount of ‘home made lye’ it wouldn’t saponify. If there is more lye than oil, it could hurt the skin. Potassium hydroxide is used for making liquid soaps and soft shaving soaps and you won’t really get a hard bar out of it. A soap calculator is the best way to determine how much lye to use based on the amount of oils and butters you are using. Always use caution.

It takes a LOT of trial and error to get a good, firmish soap. The annoying part is that, unless you are really diligent and keep a diary of things (what type of wood ash was used, how long you let the boiled ashes sit, etc.), it’s hard to know what things worked and what didn’t. Personally, I don’t make soap for everyday life. It was more of an experiment and a way to practice a skill that would be valuable in a SHTF situation.

“When the mixture is golden brown and doesn’t make streaks when stirred, it is ready for pouring. It might take several hours before it is ready. Keep it warm during this time!

You’ll know the soap is ready to be poured when you draw a line across it with your spoon and see a line.”

I find it this contradictionary. Mixture is ready for pouring, when it at the same time makes and doesn’t make streaks when stirred. How it can be both at the same time?

I’ll update the post to make it more clear. One is color streaks the other is physical streaks.

this is a good introduction, thank you !!! I want to make a natural soap, less caustic, mostly as a medium of delivering poppy seed oil, while still being less oily and more cleaning than just an ointment or lotion.

What kind of fat should you use and what kind should you not/never use? Can you use leftover fat from cooking or should you use clean fat? What about vegetable shortening?

I’m new to this whole thing so pardon the ignorance of these questions. Thanks in advance.

Almost any type of fatty oil can be used but they all affect the bar quality in the finished product. Palm oil can be used but if you step up to palm kernel oil it makes the bar harder. Other oils will give you better lather than others. Castor oil gives a rich bubbly lather.

I made an ash soap for a science fair in 2018, I don’t look good in soap, I look greasy and doughy. And I came to realize until 2020 that I could have added salt to it, to make it last. I think I used weak wood ash. I want to do this project again. I remember that to make it smell, I added a bath flavoring pill.

🙂 Trying is fun.

That’s awesome! I’m also a science nerd and very proud of it. 😀 Let us know if any tips you have if you try it again.

Is a Porcelain pot safe to boil the lye water?

It might depend on the porcelain, but (from what I know) it’s generally not safe to put boiling anything in porcelain because it can easily crack. I wouldn’t to risk it with lye and have it end up everywhere!

Can I drain the ly watet into plastic bucket? I don’t want to leave it to drain over night & come out to a bucket that’s been eaten through…

See this article https://classicbells.com/soap/lyeStorage.asp It goes over the types of plastic which are okay and which are very much not okay.

I want to make LIQUID ash soap for dishes & laundry. I made lye but havent concentrated it yet. Suggestions?

Does the kind of salt matter? Iodized or plain table salt, kosher, coarse…? I figure if I am spending this much time on soap I should probably make sure I am using the correct ingredients. Thanks for the article! I have been reading everything I can to work up the courage to try this. My mom said my grandma used to make homemade soap, but you never knew how strong or weak it was going to be .

Scary… lol, obviously 11 kids lived through it with no issues so it couldn’t have been too bad.

Great question! No, the type of salt doesn’t matter. You can use iodized salt, non-iodized salt, kosher salt, sea salt… The only salt which WON’T work is Epsom salt, but that isn’t actually salt (try it and your soap will end up soggy and sweating).

IMO, it isn’t worth it to use fancy salts like Himalayan pink salt in soap. These salts do contain natural minerals and thus are “healthier” (though that is debatable). However, you aren’t going to absorb minerals through your skin, so the mineral content of the salt doesn’t matter.

Good luck!

The source linked to for calculating lye to fat, and some others I happened upon, say bar soap is fat and sodium hydroxide, lye. Liquid soap is potassium hydroxide, caustic potash—derived from wood ash, historically referred to as lye but not the same thing.

I found a couple of sources that say you can still manage a soft bar with the addition of some salt. I also found some recipes for homemade lye, but I think commercial, food grade lye is probably a much safer and much better alternative, if you’re going to go through with making bar soap.

I learned why soap is so convoluted now. Manufacturers remove the glycerin, which goes on to be used in the manufacture of lotions and explosives, and they replace it with less expensive softeners. It’s like taking the peanut oil out of peanut butter and adding palm oil back in.

May I use lamb fat? If so, I just melt it?

Thanks

Yes rendered lamb fat will work.

Safety warning. If you add oil to lye, you risk splattering. The other way around is safer: Add lye to oils.

Thanks Tony, great point, I have added it to the article.

So…I botched this royally. I cooked lye water down to 3/4 cup and the added salt and oil. The mixture hasn’t thickened at all. Instead, crystals formed and are sticking to the pot, and the oil is just sitting there. So, yeah.

Haha yes this is a tricky procedure, lots of places it can go wrong. Keep trying!

What kind of water did you use? Has to be distilled water only or if you can collect enough rainwater that hasnt come into contact with any pollutants

I got thick soap base like batter. But it oil came separately after i added dried herbals .

Could you please let me know what could the reason

Thanks in advance

Unfortunately there is a lot of trial and error involved in this process. Impossible to say what the problem might be, have you tried some of the toubleshooting tips above ie adding more lye?

Made a soap mixture that was soft, had brown liquid separate in the mold. Left it to set for several weeks stayed a thick paste. Eventually crystals started to form on it.

Seemed to burn skin a little too.

I could find very little information to go on so I did some guessing.

For instance, trying to float a raw egg on boiling lye was inconclusive. The egg would float at the top below the surface then sank. Not on top. I imagine it sank because it was cooking thru.

I could not figure how far to reduce the lye. Starred with about two gallons and reduced it to about two cups.

One recipe I read seemed to say I was supposed to put water into it before adding the fat. That made no sense to me so I didn’t.

I could only go by the texture as to how much fat I would need. After reading yours I’m guessing I didn’t use enough.

Only used a little salt. Coconut oil.

Definitely some trial and error involved as there are so many variables. Let us know if you get some good results.

I started making soap 2 years ago. I find it very satisfying, however being a working parent I also need to find time. It takes time and plenty of stirring to set up the soap. My father used to help his mother make soap as a child. Helping mom by stirring the soap.was a job he had to do but I wont let my little ones do this as the soap is caustic and I havent perfected my recipe yet.

Also a tip: I use thrift store crock pots. No worries about what they are made of. There is no metal involved.

This is really interesting and a well written article. I am hoping to do this someday soon.